In 1982, the UN-Working Group on Indigenous Populations offered a first preliminary definition of “[i]ndigenous communities, peoples, and nations” as “those that, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them”, adding that “[t]hey form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.”

Colloquially, members of indigenous peoples have long been referred to as “savages”, “tribals” or, in the context of the Americas, “Indians”. All these terms are deeply rooted in colonialism, the eurocentric perceptions, discriminatory, demeaning, and genocidal practices. The violent conquest, subjugation and enslavement by predominantly European powers has left indelible bloody marks in the history and present of African, Asian and pre-Columbian American communities and nations. Therefore, language that reflects its underlying mindset should be rejected and avoided.

Internationally, “indigenous” has established itself as the most common designation, and - generally maintaining the criteria established in 1982 - is also being used by the UN-Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issue (UNFPII). However, since it intentionally or unintentionally often carries connotations of a lesser degree of “development” (another term under increasingly controversial scrutiny), it is also subject to criticism. Other terms that have been brought forward are “first nations” (especially in the North American context), “ancestral peoples” or the Spanish “pueblos originarios”. By ways of conclusion, there is no one “correct” term, and different people from different backgrounds are favoring or criticizing different designations for different reasons.

At OroVerde, we have decided to adopt those terms that the people we actively cooperate with (mainly meaning the Kichwa of Sarayaku and the Shipibo-Konibo organized in the Federación de Comunidades Nativas del Ucayali y Afluentes (FECONAU) in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon region as well as the Guatemaltecan communities represented in Sotz’il) prefer to describe themselves. Thus, we speak of “indigenous peoples” and “pueblos originarios”.

Why so much hassle about terms and definitions?

The recognition as “indigenous” confers special rights under international law as well as under many national legislations. Therefore, this at first glance theoretical discussion carries significant and concrete legal consequences. These include for example the recognition of inalienable, unsellable, and imprescriptible collective land rights or the right to prior informed and legally binding consultation on public or private projects planned on indigenous territory.

Nonetheless, it’s important to note that all these terms remain preliminary working definitions. Neither the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples passed in 2007 after 20 years in the making nor the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of the International Labour Organization (ILO-Convention No. 169) give a fixed definition. Instead, they stress the right of groups and individuals to self-identify as indigenous as essential. They thereby consciously distance themselves from the colonialist history of forcing external preconceptions upon indigenous peoples and individuals.

Indigenous peoples around the world

Indigenous peoples exist around the world on all continents. Well-known examples are Aboriginal Australians (yet another hotly debated term), Inuit in Canada and Greenland, the First Nations of Northern America, Tuareg in the Sahara and Sahel regions, Ainu in Japan, Adivasi in India, Maori in New Zealand, Sámi in Scandinavia, or the many pueblos originarios of the Amazon basin, among them Kichwa and Shipibo-Konibo. A special case are the Sentinelese on North Sentinel Island, a small island in the Indian Ocean, who are actively rejecting interaction with the outside world. The Indian government has prohibited travel to the island.

Modern tradition

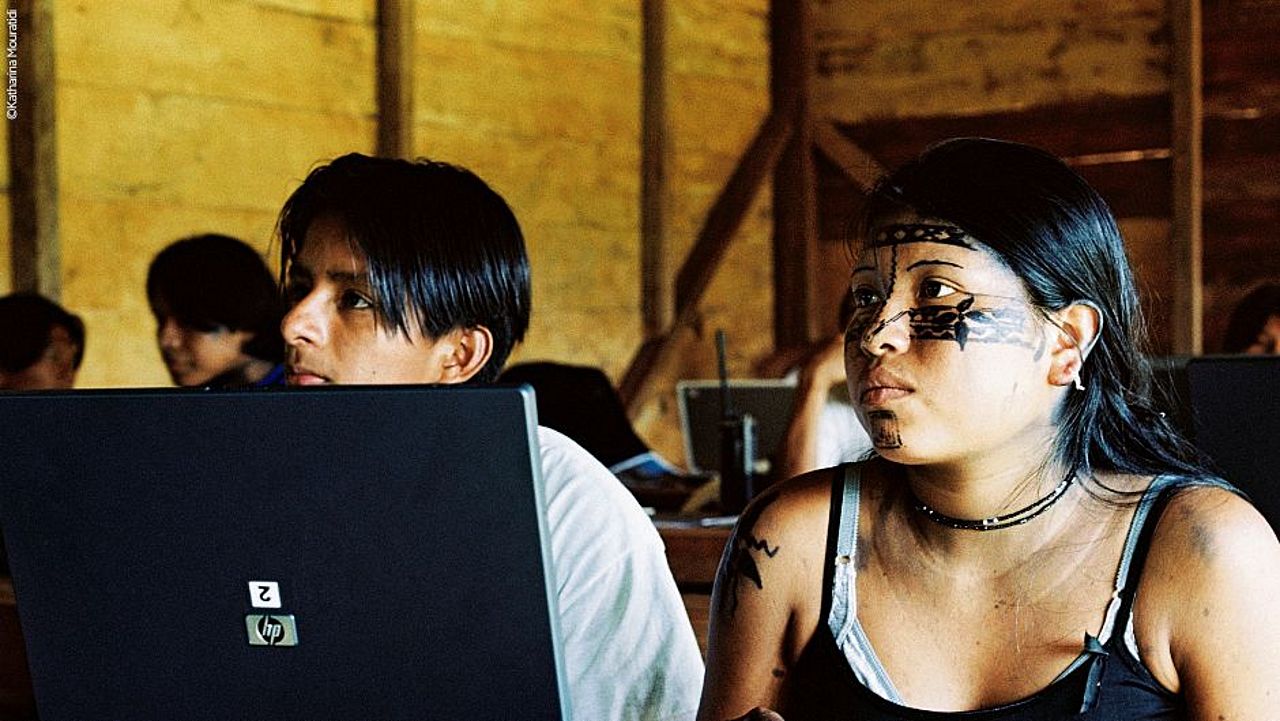

It is important to recognize that indigenous culture and lifestyle are not set in stone for all eternity. Like all human communities, indigenous peoples change to ensure survival in adaptation to their environment or ins response to internal motivation and developments. Just like for other cultures and communities, the pressure to adapt has increased during the last decades through globalization, global crises like climate change or the accelerating destruction of natural resources on which their livelihoods are based. In these accelerating processes of change, the decisions on what is essential to their identity and lifestyle and where new strategies are needed to preserve just this essence is a difficult balancing act, in particular for indigenous youth.

Indigenous communities are crucial allies for the conservation of tropical forests.

The territories of many indigenous peoples are situated in relatively well-preserved environments like rainforests or the Arctic. There, they have developed survival strategies and economies in harmony with nature which have served them well for centuries, but nowadays are increasingly under pressure. Especially for the conservation of forests, indigenous communities are important allies. A 2021 summary of the most important scientific findings on the contributions of indigenous peoples to forest and climate protection by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Fund for the Development of Indigenous Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean determined that more than 80 percent of territories inhabited by indigenous peoples in Latin America and the Caribbean are covered by forest. 45 percent of still intact Amazonian forests are located on indigenous territory.

Successful cooperation with indigenous peoples and Pueblos Originarios

Even though indigenous communities are frequently more successful than others in protecting their territories from illegal and unsustainable exploitation, the territories and with them their inhabitants and their livelihoods are facing constant and increasing threats. The destruction of rainforests or the melting of Arctic ice not only threatens the survival not only of many plant and animal species but also of indigenous peoples and their culture. They are forced to give up their traditional livelihoods, which also leads to the loss of traditional knowledge carried only by indigenous peoples. The contributions of indigenous peoples to the conservation of natural resources and the high significance of their traditional knowledge for global challenges like the mitigation of climate change or the protection of biodiversity are finally being recognized on a more regular basis. For instance, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that “respectful dialogue between Indigenous knowledge and local knowledge and modern science” is crucial to successful adaption to climate change. Therefore, it is crucial to strengthen the recognition of indigenous peoples’ contributions to biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation as well as the effective implementation of their rights, for example through expanding the right to consultation on projects, that affect their territories, towards active participation and – in case of doubt – veto rights.

At OroVerde, we strive to support our indigenous partner organizations and communities in this endeavor to the best of our abilities and are grateful for every step we share on the path of mutual and collaborative learning.

Do you have any questions?

We are here to help!

OroVerde - Tropical Forest Foundation

+49 228 24290-0

info[at]oroverde[dot]de

Photo credits: Sarayaku.js (header), Jonas Rüger (Guardia Indígena and mural indigenous resistance) , OroVerde - M.Baumann (boat on rain forest-river), Katharina Mouratidi (indigenous youth with laptop laptop), OroVerde - A.Fincke (indigenous rappers)